The Patient’s Complaint

Case studies, including this one, help us understand how the Courts have interpreted and applied law, to resolve real world disputes – creating precedents that may be followed in the future.

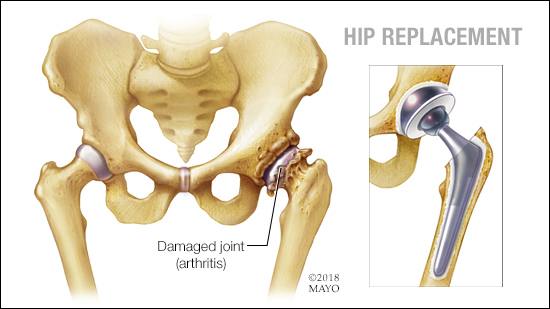

Depuy developed the Pinnacle metal on metal (MoM) hip, for younger and more active patients needing a ‘robust and durable’ hip replacement, as the result of traumatic injury or osteoarthritis.

Although most of the patients who received the Pinnacle MoM hip were pleased with them, a significant minority – including Ian Haley – developed an Adverse Reaction the Metal Debris (ARMD), as their immune system reacted to metallic wear particles from the hip’s bearing surfaces.

In 2018 a group of 312 patients, including Ian Haley, sued Depuy in the English High Court for compensation, claiming that they were harmed because the Pinnacle MoM hip was ‘legally defective’. So, what can learn from how they presented their case?

The patients’ complaint against Depuy

Although the patients seeking compensation from Depuy were critical of the design of the Pinnacle MoM hip, they didn’t accuse Depuy of negligence, or lack of care in it’s design and production. Nor did they identify any engineering defect in the hips that failed – which apparently complied with the design specification.

Instead they based their case on the European Product Liability Directive, implemented in UK law by Part 1 of the Consumer Protection Act. This allows consumers to obtain compensation for any harm, loss or injury caused by a product that is unsafe or legally defective – without the need to prove that the producer was ‘at fault’.

Article 6, of the EU Directive reads:-

1) A product is defective when it does not provide the safety which a

person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account,

including:(a) The presentation of the product

(b) The use to which it could reasonably be expected it would be put

(c) The time when the product was put into circulation (or introduced to the market)

2) A product shall not be considered defective for the sole reason that a better product is subsequently put into circulation

EU Product Liability Directive – Article 6

The Directive also says that:-

If the consumer can prove that the product was in fact defective, and the defect caused their loss or injury, then the producer is strictly liable for that loss, subject to the following limitations:-

- Claims must be submitted to the Court before the tenth anniversary of the date on which the defective product was supplied, and within three years of the loss occurring or being discovered.

- The producer may use any of the six permitted defence arguments set out in Article 7 of the Directive

However, engineers and lawyers give the word defect different meanings. Engineers use the word Defect to describe an attribute or characteristics of a part that does not comply with the specification or a loss or change in performance- for example:-

- The seat cover is stained, split or torn and can’t be used

- The hole has been drilled in the wrong place

- The engine does not deliver ‘full power’

Many of these engineering defects can exist in the product, without making it legally defective – because they don’t compromise the consumers safety – within 10 years of the product being sold or supplied to the consumer..

However, when a product does not provide the level of safety that the public are entitled to expect, it will be legally defective even when it fully complies with the design specification.

The patients primary claim against Depuy

The patients’ first, or primary claim against Depuy described the defect as the ‘MoM Hip’s tendency to shed metallic wear particles from the bearing surface’ – and the harm was described as – ‘the Patients developing ARMD as a reaction to those particles, requiring revision surgery to replace the hip joint’.

Describing the problem like this sounds familiar to engineers who use Failure Modes Effects Analysis (FMEA) – to identify the need for design and process improvements – or controls – to prevent, detect and mitigate potential failures. It identifies the defect as the characteristic of the product that may cause harm. and the consequences or effects of the defect as the potential harm. In this case;-

- There was evidence of metallic wear particles embedded in soft tissue around the patients’ hip joints

- Pseudo-tumors had formed around those particles in some patients

- Some patients had abnormally high level of chrome and cobalt in their blood stream, absorbed from metallic wear particles

- Some of the patients required revision surgery to replace or repair the Pinnacle MoM Hip within ten years of receiving it, as a result of ARMD

Framing their complaint in this way, focuses attention on the experience of individual patients, their clinical symptoms and the mechanism or process of ‘failure’.

The patients’ secondary claim against Depuy

The patients also presented an alternative argument, in case their first one was rejected by the Court. This was that;- The Pinnacle MoM hip was defective because, the risk of complications requiring revision surgery within 10 years, was higher than they were entitled to expect.

Presenting this argument focuses attention on the statistical risk or probability of failure, – attempting to show that the failure rate of the MoM Pinnacle hip was significantly higher than expected, and that they were among the ‘excess failures’.

Depuy’s Defence

Depuy denied any liability for the harm caused to patients who received Pinnacle MoM hips and subsequently required revision surgery as a result of an Adverse Reaction to Metallic Debris (ARMD), on the grounds that:-

- The Pinnacle MoM hip was not legally defective because, considering all the circumstances, it provided the level of safety that patients were entitled to expect, when the design was introduced to the market in 2000.

- But, even if the MoM Hip was found to be defective, the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time could not have detected the defect, without clinical experience of it’s use in patients who were hyper-sensitive to metallic wear particles, and would later develop ARMD

Known as the the ‘development risk defence’, the defence that:- “The defect – or lack of safety – could not have been detected before the product was launched, using the best scientific and technical knowledge available” – is permitted by Article 7 of the EU Directive. Although, EU States can limit it’s use by national legislation, it is available in the UK.

The Judge’s reasoning

People involved in product design or introducing new technology to the market may debate:-

- What level of safety are the public entitled to expect?

- When does a product become legally defective?

The Judge in this case, the Honourable Mrs Justice Andrews answers those questions in her written judgement – and her reasoning provides a precedent that may be followed in future.

So in my next post, coming soon we will explore her reasoning …

To learn more…

To learn more about Product Liability and risk management please contact Phil Stunell or subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates.