How to Prove Products are Defective

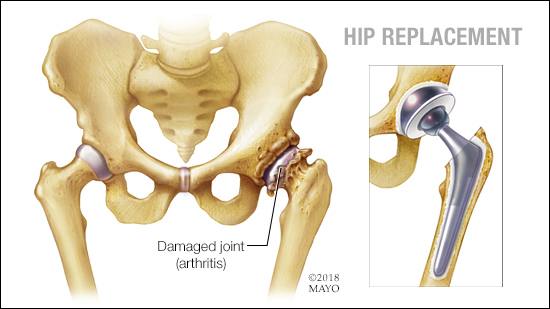

The 312 patients, including Ian Haley, seeking compensation from Depuy claimed that their Pinnacle Metal on Metal (MoM) hips were defective, because:-

- Metallic wear particles were shed from bearing surfaces

- Their immune systems reacted to the metallic debris, causing pseudo tumours to develop, damaging their muscle and bone structure – a process described as ARMD (Adverse Reaction to Metallic Debris)

- As a result of ARMD, they required revision surgery to remove and replace their Pinnacle MoM hips, in some cases leaving them with a permanent disability

They did not claim that Depuy had been negligent or failed in their Duty of Care. Instead their claim was made under Part 1 of the Consumer Protect Act (CPA), which implements the European Product Liability Directive in British law.

The Directive says that a producer is strictly – without fault – liable for any harm caused by defects in the products they supply to consumers, and defines a defect by saying:-

1) A product is defective when it does not provide the safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account, including:-

a) the presentation of the product

b) the use to which it could reasonably be expected that the product would be put

c) the time when the product was put into circulation

2) A product shall not be considered defective for the sole reason that a better product is subsequently put into circulation

Article 6 of 85/374/EEC as amended by Directive 1999/34/EC

If the patients succeeded in proving that:-

- The product was defective

- They suffered the harm

- The defect cause the harm

Then Depuy would be liable for any damage caused by the defect, unless they could use one of the defence arguments permitted by Article 7 of the Directive.

So, the claimants presented two alternative explanations of the defect.

As discussed in my previous post in their primary claim, which was unsuccessful they argued that:-

- The defect was the production of metallic wear particles from the bearing surfaces of the hip joint,

- The harm caused was the need for revision surgery and any resultant disability, pain and discomfort

However, knowing that Depuy might object to that definition of the defect they also presented a second alternative claim, that:-

“…the Pinnacle Ultamet prosthesis had an abnormal potential for damage, compared with existing established non-MoM total hip replacement prostheses and/or that a large head MoM articulation had an abnormal potential for damage compared to alternative bearing surfaces within the Pinnacle modular system”

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 136

While their primary case against Depuy focused on the experience of individual patients and their reaction to metallic debris, this alternative claim was about the ‘statistical risk’ that a patient would require revision surgery.

In her written judgement Mrs Justice Andrews, explains how she decided if that risk was unacceptably high – which if proven would make the Pinnacle MoM hip legally defective.

So let’s follow her reasoning –

What should the public expect?

The Directive says that “A product is defective when it does not provide the level of safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account, including”

- The presentation of the product

- The use to which it could reasonably be expected that the product would be put

- The time when the product was put into circulation

So, in order to decide if a defect exists the Court must first decide what level of safety the public were entitled to expect, and that requires the Court to consider the all the relevant circumstances.

So which circumstances are relevant?

Justice Andrews agreed with previous judgements that the circumstances taken into account must be legally and factually relevant to the particular case, but what are they?

Both sides agreed that the circumstances listed in the Directive must be considered by the Court, and may be the most significant, but they disagreed about what else should be considered. So, Mrs Justice Andrews explained her approach .

The claimants argued the Court should exclude some circumstances, because in a previous case, involving contaminated blood products, (A v NBA), Justice Burton had ruled that they were not relevant in that case, when deciding the level of safety the public were entitled to expect.

But rejecting their argument Justice Andrews wrote:-

In general, I prefer Hickinbottom J’s approach in Wilkes to that of Burton J in A v NBA. I agree with Hickinbottom J’s observations in Wilkes at [77] to [79], especially that:

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 143

“the court must maintain a flexible approach to the assessment of the appropriate level of safety, including which circumstances are relevant and the weight to be given to each, those factors being quintessentially dependent upon the particular facts of any case.”

So, the Judges can use their discretion to consider any circumstance that is factually and legally relevant when deciding the level of safety the public are entitled to expect.

So what did Justice Andrews consider in this case and why:-

Whose expectations of safety?

When deciding if a product is defective, the Court must decide the level of safety the public are entitled to expect

So, this is not a debate about what the claimants actually expected, but the nature and level of risk that the public should accept, given the nature of the product and the relevant circumstances.

What did their surgeons know?

Medical devices such as hip implants are not sold directly to the public, instead they are selected and recommended by a surgeon who is expected to know more than the general public about the risks and benefits of alternative treatments.

Patients are also required to give their informed consent before having surgery, but they may rely on the advice of medical practitioners, or ‘learned intermediaries’ – when giving consent.

So is the Court trying to decide:-

- What the Surgeon should have anticipated? or

- What the patients were entitled to expect?

Mrs Justice Andrews agreed with the claimants that:-

……. in assessing safety, the focus must be on what the public generally are entitled to expect, not what clinicians are entitled to expect, but the latter may have a considerable bearing on the former.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 169

However she also agreed with Depuy that:-

Where a product is not defective, the (legal) regime is not designed to classify it as defective because of some fault or failing on the part of the intermediary (for example, a failure to pass on warnings or obtain properly informed consent).

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 169

Because the producer of the medical device is not be liable for any lack of care or negligence by the medical staff, when giving advice or performing surgery, although the patients may have a claim separate against them for medical negligence.

How was the product presented?

The Court will consider the nature of the product and it’s intended use, as well as any information supplied with the product, for example instructions for use, or warnings given to users.

When was the product introduced?

The Court will decide the level of safety the public were entitled to expect ‘at the time the product was introduced to the market‘.

These expectations of safety will not be upgraded as newer and better products are introduced to the market, because:-

“A product shall not be considered defective for the sole reason that a better product is subsequently put into circulation”

EU Product Liability Directive, Article 6 – 2

However the public’s expectations of safety may be reset if a ‘new and improved’ version of the product is introduced, and the Court would then have decide if the modified product was actually ‘an new product being put into circulation’.

But a product considered safe, may become defective as a result of changes that occur after it has been introduced to the market, for example errors in production, or design modifications that increase the risk of harm in a ‘safe product’ may make some. or all, of them defective.

It may also take some time, possibly years, before some defects are recognised as an unacceptable risk to public safety, for example latent defects such as fatigue failures or corrosion will take time to develop. So, when deciding if the product is actually defective the court will also consider what what has been learnt since it was introduced and the circumstances of the complaint.

Was the producer at ‘fault’ or negligent?

As the Directive introduces a system of ‘liability without fault’ – or strict liability – claimants are not required to identify the producer’s ‘fault’ – or lack of care – and any potential negligence is irrelevant when deciding the level of safety to be expected.

So, although the Court will be interested in the characteristics of the product that make it defective, how those characteristic came into being is not relevant when deciding the issue of liability under the Directive. (Unlike claims for Negligence)

Did it comply with the specification?

Although the public are entitled to expect all products to comply with their specification, a product that doesn’t might, or might not, increase the risk of harm to users.

So. we can’t assume that a product that doesn’t comply with the specification is defective, the claimants must prove that any increased risk of harm has become unacceptably high.

According to Justice Andrews –

There is no distinction drawn in the Directive, or in the Act, between different types of product – “standard” (conforming) or “non-standard” (non-conforming), for example, or between different types of defect – such as a manufacturing defect, a design defect or a warning defect, as in the US system. The definition of “defect” applies across the board, and the sole issue for the Court in determining whether a product is defective or not is whether it meets the standard of safety set out in section 3 of the Act. (Article 6 of the Directive)

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 93

Referring to previous cases involving non-standard, or non-conforming, products, Justice Andrews concluded that:-

Both Justice Burton and Justice Hickinbottom rightly acknowledged that it may be easier to prove that a product is defective if it is out of specification, but they also acknowledged that the mere fact that it is out of specification may not be enough to prove that it lacks the requisite degree of safety. Conversely, a product that meets its specification may still be unsafe when evaluated by the objective test in Section 3 of the Consumer Protection Act (or Article 6 of the Directive)

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 159

And as she went on to explain:-

The fact that a product fails following normal use and in circumstances in which a standard (conforming) product would not have failed may suffice for the Court to draw the inference that it is defective, see e.g. Ide v ATB Sales Ltd and Another [2008] EWCA Civ 424. Thus, for example, if an electrical appliance bursts into flames if it is left plugged in, or a fridge explodes, it plainly does not meet the standard of safety that persons generally are entitled to expect, and it is unnecessary for the claimant to establish what caused it to catch fire or explode.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 99

But:-

…..if the injury or damage complained of could have arisen even if the product met the objective standard of safety set out in section 3 of the Act, (Article 6 of the Directive) for example, in consequence of the manifestation of a known risk that could arise in normal use. Then the claimant may have to establish that the failure of a product or a component in it was not due to ordinary wear and tear, but to something abnormal that caused it to fail when it should not have done; or that something must have happened to elevate the inherent risk to a level that was higher than the public was entitled to expect.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 100

So it may be more difficult to prove the product was defective when an known risk materialises, if you can’t identify any abnormality that caused the failure and resultant injury.

What about regulations?

Justice Andrews observed that:-

No-one has suggested that compliance with standards or regulations affords a defence or creates any prima facie presumption in favour of the producer (that the product is safe). The weight to be ascribed to these factors will depend on the facts and circumstances of the individual case.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 173

So. according to Justice Andrews compliance with regulations is relevant when assessing the safety of the product, but:-

….. the standards set by a regulatory regime cannot be used as a substitute for the statutory test of safety (in Article 6), even when the regulatory regime expressly addresses safety. The level of safety that the public is entitled to expect may be lower than a particular safety standard, as in Pollard v Tesco Stores, where the British safety standard for childproof caps on which the claimants sought to rely did not apply to dishwater powder bottles, because there was no requirement at the time that such products should have a childproof cap. In other cases, it may be higher, for example if the product complied in all material respects with particular safety features required by the regulatory regime, but there was some additional feature that made it unsafe; or where the generic products complied with the regulatory regime but there was a faulty batch that would have failed the safety assessment, as in Boston Scientific (a case involving a batch of faulty defibrillators) . The weight to be placed on such compliance is a matter of fact and degree in the individual case, and it may be of no relevance at all.

Pinnacle judgement Paragraph 175

Justice Andrews then observed that:-

In the pinnacle MoM litigation, the complaint relates to something that is not directly addressed in any safety standard or regulation, nor could it be, because the state of science is such that it is impossible to set any product specifications which would have a direct impact on the incidence of ARMD. For that reason, compliance with regulatory requirements may not play as significant a part in the overall assessment of defectiveness as it did in a case such as Wilkes. (another case against Depuy)

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 178

Can potential benefits justify the risk?

Justice Andrews reviewed the legal arguments and precedents about the use of a Risk – Benefit Analysis when evaluating the levels of safety the public are entitled to expect and concluded that:-

If the use to which the product can reasonably be expected to be put is a relevant consideration, as it undoubtedly is, then it cannot be objectionable for the Court to consider the benefits likely to arise from its contemplated use as part and parcel of the circumstances that have a bearing on the evaluation of the level of safety that the public generally is entitled to expect.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 164

In the context of medical devices, that are intended to maintain or improve your quality of live, it is reasonable that the public would balance the risk of known side effects against the expected benefits of treatment – before giving their informed consent and accepting those risks.

But, because they claimed that the the metal-on-metal hip was developed to reduce the known risks in alternative designs – such as dislocation and fatigue failures;- Depuy also wanted the Court to consider the risk of revision surgery from all causes, rather than only the incidence of revision surgery due to ARMD.

So Depuy argued that:-

….where a product includes a feature which gives it a potential functional advantage, or eliminates a perceived deficiency in design, but by doing so necessarily introduces a risk, it is artificial to prevent the Court from considering that actual or potential benefit when making an assessment of whether the product is defective.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 153 a

And Justice Andrews answered saying:-

Depending on the circumstances, including any warnings, the safety risk may be one that, objectively, the public would be expected to accept, bearing in mind the benefits that the product would confer. Much will depend on the nature and seriousness of the risk and the likelihood of its manifestation.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 153 b

So, a defect may be defined by the undesirable effect on the user, and the unacceptably high chance that it will occur – considering all the failure modes that could result in that outcome.

Did the defect actually cause the loss?

According to the Directive, the claimants are required not only to establish that the product was defective, but also that the defect caused their loss or injury. So Mrs Justice Andrews explained how this could be achieved.

She noted that:-

The patient’s complaint is that Pinnacle Ultamet prosthesis carried a materially increased risk of early failure because of ARMD, requiring revision surgery. It is common ground that all hip prostheses have an underlying risk of failure, requiring revision, within 10 years. Therefore, each claimant must prove that the increased risk was what caused them to undergo the early revision, rather than the inherent risk of failure leading to early revision that would arise irrespective of that defect.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 180

So for the claimants, the challenge was not to show that ‘more people than expected required revision surgery’ – but that – on the balance of probabilities they, as individuals, only required revision surgery because the hip they received was defective.

In personal injury cases based on negligence the claimant would normally be asked to prove that the loss would not have occurred, ‘but for‘ the defendants negligence. The same reasoning can be applied to strict liability claims when the defect is the result of some abnormality that introduces a ‘new risk’. In those cases, the claimant could argue:-

The loss would not have occurred but for the abnormality

However, it becomes more difficult to apply that logic if the complaint relates to an ‘unexpectedly high rate of occurrence’ of a known risk that would normally – at a lower rate of occurrence – be accepted by the public.

Depuy argued that the correct test in those circumstances should be:-

Does the defect double the risk of harm?

Their logic being that, if the risk was more than doubled by the existence of the defect, then more than 50% of the patients with ARMD who required revision surgery probably had revision surgery due to the defect. So, for individual patients in that group it would be more likely than not that their revision surgery was due to the defect,

But the claimants disagreed, arguing that, the damage was the revision surgery in whole in part due to ARMD. So the correct question for the Court to ask would be:-

…..whether a claimant would have suffered ARMD (and not whether the claimant would have undergone a revision for an early failure) if he or she had had an implant that did not create the abnormal potential for damage of that type. They submitted that because the adverse reaction manifests itself in soft tissue damage, and for causation purposes the Court is concerned with the causal connection between that defect and the damage of which the claimant is complaining, the question is whether, if the claimant had a different type of prosthesis implanted, they would have been revised for ARMD.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 184

But that argument was rejected by the Judge because:-

…..The correct question for the Court to ask is whether, on the balance of probabilities, the claimant would have suffered the damage complained of, i.e. undergone an early revision, if the hip had not carried with it the increased risk of early failure which made it defective. That means the appropriate comparison is with the generic incidence of early failure, and not just failure for ARMD.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 185

So Justice Andrews Concluded that:-

If it were to be established that the incidence of early failure of Pinnacle Ultamet (MoM) hips by reason of ARMD was more than double the general incidence of early failure of comparator hip prostheses, then of course the claimant would discharge the burden of proving causation. However, I am not persuaded that this is the only way in which causation could be established, or that “more than double the risk” should be adopted as a bright-line test in a case such as this…

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 186

What can you compare it to?

When deciding the level of safety the public are entitled to expect, the Court may compare a product with other products of the same generic type – that are already accepted in the market place.

This helps the Judge understand:-

- The risks that are normally associated with that type of product.

- The level of risk that the general public have already accepted when using products of that type, which will be informed by their experience of products already on the market.

Claimants would obviously want to use comparator that is as ‘safe as possible’ – while the producer will draw attention to the risks already accepted by the general public in competing products.

Depuy said that the Pinnacle MoM hips should be compared with hip joints that were already on the market in 2002, when the pinnacle range was launched, as they would have been available as ‘an alternative choice’ at that time.

The patients argued that:-

- The MoM Pinnacle Hip should be compared with the metal on plastic (MoP) and Metal on Ceramic (MoC) hips in the Pinnacle range that were launched at the same time by Depuy. (Which had proved to be exceptionally durable and resilient in normal use).

- As Depuy had promoted the Pinnacle MoM hip as an ‘improvement on existing designs’ and therefore the general public were entitled to expect that it would in fact be safer than those alternative designs already on the market

But Justice Andrews was unimpressed by those arguments, because:-

- In 2002, the public expectations of safety could not informed or influenced by the unproven reliability and durability of a product that had not yet entered the market. So a comparison with other versions of the Pinnacle hip would be inappropriate.

- Surgeons and patients alike believed that the new generation of MoM hip prostheses would survive for longer than the existing, predominantly MoP designs. That was also Depuy’s aspiration. Whilst it was hoped that the new generation of hip implants would be an improvement on the existing products in this and various other respects, when they were launched on the market it was not known how well they would perform in real life. A failure to meet aspirations does not equate to a lack of safety.

What about the evidence?

In her written Judgement Justice Andrews explained the law, and how it applied in this case, before turning her attention to the evidence presented in court.

So we will examine the facts of the case in more detail in my next article.

To learn more…

When we deliver Product Liability Training we use case studies to help us explain how the Courts have interpreted and applied the law.

However, the Judges reasoning also provides a ‘model answer’, or judicial precedent, that may be followed in the future.

To learn more about Product Liability and risk management please contact Phil Stunell or subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates.

Leave a Reply