Legal Argument – What is a Defect?

In 2018 a group of 312 patients including Ian Haley, who had received artificial hips manufactured by Depuy, sued Depuy in the English High Court claiming that:-

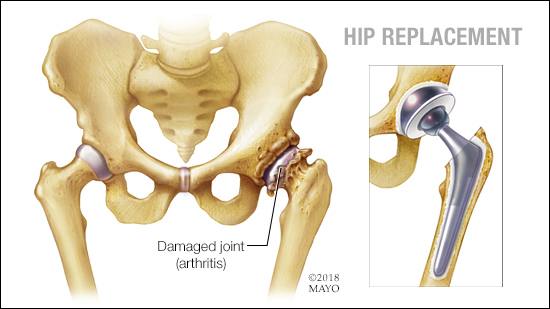

- The Pinnacle Hips with a Metal on Metal (MoM) bearings were legally defective, because the patient’s immune system reacted to microscopic wear particles from the bearing surfaces of the joint.

- Typically, their Adverse Reaction to Metallic Debris (ARMD) caused the growth of pseudo tumors in the soft tissue around the joint, and damaged their muscles and bone structure – among other symptoms.

- Patients with severe ARMD required revision surgery to remove and replace their Pinnacle MoM hips. In some cases leaving them with reduced mobility or a permanent disability.

But, the patients did not attempt to prove that Depuy had been negligent, or failed to exercise their Duty of Care

Instead they based their claim against Depuy on the European Product Liability Directive, which has been implemented in British Law by Part 1 of the Consumer Protection Act (CPA).

So in her written judgement the Judge, the Honourable Mrs Justice Andrews analysed the law, explaining how it should be applied – creating a precedent or example that may be used in future.

The Product Liability Directive

The Product Liability Directive was introduced in 1985, because the European Council recognised that the patch work quilt of legislation across Europe needed to be harmonised to:-

- Balance the economic interests of consumers and producers

- Enhance consumer protection

Reading the EU Directive, you will find:-

- The preamble or Recitals, which explain the European Council’s policy objectives and the purpose of the Directive.

- Articles, which define the rules to be implemented in the domestic law of the member states.

Although we may be tempted to fast forward through the Recitals – that is a mistake. The Articles are intended achieve the policy objectives explained in the Recitals – so the Articles must be interpreted in a way that achieves, as far as possible, those policy objectives.

Unlike Regulations that apply directly in the EU member states, directives must be implemented by domestic legislation in each country. So, Part 1 of the Consumer Protection Act (CPA) implements the Directive in the UK and must also be interpreted to achieve the purpose of the Directive.

Before the Directive was introduced, consumers who were harmed by dangerous or unsafe products could only seek compensation based on:-

- Contract Law – and Breach of Contract

- The producer’s General Duty of Care – and Claims For Negligence

These ‘fault based’ systems of civil liability require consumers seeking compensation to explain what the producer has done wrong – and in the case of negligence – how the producer could have prevented their loss or injury. But, as products and production processes become more complex – this burden of proof may prevent consumers — without the technical or financial resources to present their case – ‘getting justice’.

To address this apparent inequality between producers and consumers, the European Council concluded that:-

“…liability without fault on the part of the producer is the sole means of adequately solving the problem, peculiar to our age of increasing technicality, of a fair apportionment of the risks inherent in modern technological production”

Recital 2 of EU Product Liability Directive

So, the Directive establishes a general principle that producers are liable for any harm caused by a ‘lack of safety’ in the products they supply. This liability is created by their role as a producer of the product, or it’s component parts.

In Article 6, the Directive states that:-

1) A product is defective when it does not provide the safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account, including:-

a) the presentation of the product

b) the use to which it could reasonably be expected that the product would be put

c) the time when the product was put into circulation

2) A product shall not be considered defective for the sole reason that a better product is subsequently put into circulation

Article 6 of 85/374/EEC as amended by Directive 1999/34/EC

In general use the word defect may be used to describe what is wrong with a product or component that is not working or has been wrongly made. But the Directive gives Defect a more specific legal meaning – it is the lack of safety in the product.

According Article 4 of the Directive, to establish their claim the consumers only need to prove that:-

- The defect existed

- The damage has occurred

- The defect caused the damage

When deciding if a defect actually exists the Court must consider the safety of the product in normal use, as explained in the Recitals:-

“….the defectiveness of the product should be determined by reference not to its fitness for use but to the lack of the safety which the public at large is entitled to expect; whereas the safety is assessed by excluding any misuse of the product not reasonable under the circumstances;”

Recital 6 of the EU Product Liability Directive

But, it is the claimant’s responsibility to identify and describe the defect in a way that can convince the Judge that a ‘lack of safety’ existed – and caused their loss or injury.

Permitted Defence Arguments

Although the Directive is intended to ‘protect consumers’ and holds producers liable when their products are defective or unsafe, it also attempts to to strike a balance between the interests of consumers and producers.

So Article 7 of the Directive sets out the arguments a producer can use in their defence, when their defective product has caused harm to the consumer, these are:-

(a) that he did not put the product into circulation; or

(b) that, having regard to the circumstances, it is probable that the defect which caused the damage did not exist at the time when the product was put into circulation by him or that this defect came into being afterwards; or

(c) that the product was neither manufactured by him for sale or any form of distribution for economic purpose nor manufactured or distributed by him in the course of his business; or

(d) that the defect is due to compliance of the product with mandatory

regulations issued by the public authorities; or(e) that the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time when the put the product into circulation was not such as to enable the existence of the defect to be discovered; or

(f) in the case of a manufacturer of a component, that the defect is attributable to the design of the product in which the component has been fitted or to the instructions given by the manufacturer of the product.

From Article 7 of EU Product Liability Directive

But producers are Strictly Liable for any harm caused by defects in their product unless they can use one of these permitted defence arguments, and the court will not entertain any other arguments.

However, they only need a ‘defence’ if the Judge is convinced the defect actually existed and caused the damage – so the precise definition the defect becomes critical to the claimant’s success

Defining the Defect

The claimant’s first attempt to persuade the Judge that their hips were defective explained the ‘failure mode’ in terms of cause and effect:-

- Metallic wear particles were produced from the bearing surfaces

- The patient’s immune system reacted to those wear particles and produced pseudo-tumors and other symptoms described as ARMD.

- The patients required revision surgery to replace their ‘defective hips’, because the wear particles came from the bearing surfaces.

So, they identified the defect as the production of metallic wear particles from the bearing surfaces, and the revision surgery and any resultant disability as the harm caused.

The evidence presented in Court showed that some, if not all, of the patients had suffered from a severe adverse reaction to metallic debris (ARMD), and required revision surgery as a result – but Depuy’s response was that the claimants had not described a defect.

So in her written Judgement Justice Andrews explained how Defects can be identified and described, based on the Directive and examples from the past.

Justice Andrews observed that Article 6 of the Directive defines a defect as a lack or safety, or abnormally high risk of harm, associated with the products use, that is incompatible with the level of safety the consumer is entitled to expect.

Given that ‘absolute safety’ is rarely achievable in the real world of product design and manufacturing, the Courts must decide:-

- Considering all relevant circumstances, what level of safety are consumers entitled to expect?

- Did the product used by the consumer fail to achieve that level of safety?

The Court is not asked to decide what the consumer actually expected, or if the claimants were shocked and surprised by what happened. Instead the Court must decide how a well informed person would expect the product to perform, given all the circumstances.

So Justice Andrews reminded the Court of a previous judgement, that said:-

“the court decides what the public is entitled to expect… such objectively assessed… expectation may accord with actual expectation; but it may be more than the public actually expects, thus imposing a higher standard of safety, or it may be less than the public actually expects. Alternatively, the public may have no actual expectation – e.g. in relation to a new product.” (emphasis in the original).

Burton J: A Vs National Blood Authority [2001] 3 ALL ER 289

Depuy argued that consumers are not entitled to expect a level of safety that can not be achieved with any known technology – and since over time all bearings will wear and shed wear particles, this can not be described as a defect.

Justice Andrews agreed, saying

All hip prostheses will eventually wear out and fail, if the patient survives long enough, and some will fail within 10 years: the natural propensity of a hip implant to fail therefore cannot be a “defect,” any more than the inevitable wear and tear that causes minute particles of debris to enter the patient’s body. Otherwise all hip implants would be “defective”, irrespective of the materials used in the articulation.

Pinnacle Judgement – Paragraph 96

Although the claimants found previous examples in which the Court had accepted that a ‘product characteristic’ was a defect, the Judge concluded that these examples were special cases, because the characteristics identified as ‘defects’ were in fact abnormalities that also identified the ‘defective products’, and were directly related to an ‘expectation of safety’ and increased the risk of harm.

So, it may be significant that in this case:-

- Although the patients established that metallic wear particles were shed from the bearing surfaces, they did not argue that the particular joints they received had produced an ‘abnormal quantity’ of wear debris, or were significantly different from other hips of the same type..

- No evidence was presented to show a relationship between the quantity of wear debris produced by the joint, and the increased risk of an adverse reaction, or to suggest a safe level of exposure to metallic debris.

So, Mrs Justice Andrews rejected the claimants’s primary claim – that the production of metallic wear particles was a defect – because:-

“It ignores entirely the central question of the expectation of safety that persons generally were entitled to have of the product.”

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 106

Although they had described the ‘failure mode’ in terms of cause and effect, they had not established an expectation of safety that was not satisfied. Justice Andrews went on to explain:-

I consider the claimants’ primary approach to be directly contrary to the spirit and objectives of the Directive and the Act, which require the Court to move away from the concept of a “defect” being some flaw or failing in the product, and to concentrate instead on whether in all the circumstances the product meets the requisite objectively assessed safety standard.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 108

From the Recitals it is clear that the Directive was intended, among other things, to address situations where the claimants lacked the technical knowledge or expertise to describe the ‘failure mode’ in any technical detail. So, Article 4 of the directive only requires them to show that the product did not meet the level of safety consumers were entitled to expect, and that as result they suffered actual harm.

Inherent risks of harm

Justice Andrews then explained how the law applies when the risks of harm inherent in particular types of product have been accepted by the public and regulators, observing that:-

…..safety is inherently and necessarily a relative concept, because no product, and particularly a medicinal product, if effective, can be absolutely safe. Even such commonly prescribed medicines as penicillin or aspirin can cause a hypersensitive response in certain patients which, in an extreme case, can prove fatal. The public is not entitled to expect that a product which is known to have an inherently harmful or potentially harmful characteristic will not cause that harm, especially if (as in the present case) the product cannot be used for its intended purpose without incurring the risk of that harm materialising.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 110

In the experience of individual consumers the risk of harm has a ‘binary outcome’ – they either do or don’t suffer from it. But for producers and regulators, risk is a statistical concept, that considers the probability that the event will occur as well as it’s severity.

So, when the inherent risks of harm that have been judged acceptable, subsequently materialise we can’t describe them as defects – unless the actual rate of occurrence is higher than we were entitled to expect. As the judge explained:-

However, if the incidence of that harm, either in nature or degree, is abnormal, then the product may be regarded as falling below the standard of safety that persons generally are entitled to expect. If that is the case, the defect is not the inherently harmful characteristic which is part of the normal behaviour of the product, for so to characterise it would be to make all products of that type “defective,” as they all bear that characteristic. That is the fundamental flaw in the claimants’ original formulation. The defect is the abnormal potential for harm, i.e. whatever it is about the condition or character of the product that elevates the underlying risk beyond the level of safety that the public is entitled to expect. That approach is not a blurring of the distinction between relevant circumstances and defect as Mr Oppenheim (for the claimants) contended; it is identifying what it is about the condition or state of the product that makes it unsafe by the objective yardstick set out in section 3 of the (CPA) Act (and Article 6 of the Directive).

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 112

However, considering the facts of this particular case she also concluded that, in 2002 when the Pinnacle Ultamet (MoM) liner was launched it was already known that:-

- All hip prosthesis shed debris in the course of their normal operation.

- All MoM joints will produce some metal wear debris

- An adverse reaction to particulate debris, in general terms, could cause a hip prosthesis to fail and require revision.

So, the public had no entitlement to expect that a MoM hip will not produce metal wear debris in normal use, any more than it would be entitled to expect a Metal on Plastic hip not to produce polyethylene and/or metal debris, even though both types of debris may cause an adverse immunological reaction leading to damage to tissue or bone, and that damage may be worse or arise more quickly in some patients than others.

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 116

The Patient Secondary Claim

So, the patients primary case against Depuy was dismissed by the Judge as untenable, but they were also allowed to present their alternative or secondary argument that:-

“…the Pinnacle Ultamet prosthesis had “an abnormal potential for damage, compared with existing established non-MoM total hip replacement prostheses and/or that a large head MoM articulation had an abnormal potential for damage compared to alternative bearing surfaces within the Pinnacle modular system”

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 136

Although Depuy accepted this claim as ‘legally valid’, they said argued that it also must fail because the facts of the case did not support it, so we will examine that evidence in another article.

Justice Andrews’ judgement provides a precedent of example that may be following in future, because it clarifies the law, giving an explanation of defect and defective in the real world of product engineering

To learn more…

To learn more about Product Liability and risk management please contact Phil Stunell or subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates.

[…] my my next post, coming soon we will explore her reasoning […]

[…] discussed in my previous post in their primary claim, which was unsuccessful they argued […]